Solenoid by Mircea Cărtărescu

Sean Cotter translates another beguiling, beautiful Romanian novel

By Mircea Cărtărescu, Translated by Sean Cotter.

672 pages. Deep Vellum Publishing. $24.95.

What does one make of a book as beguiling as the Voynich Manuscript?

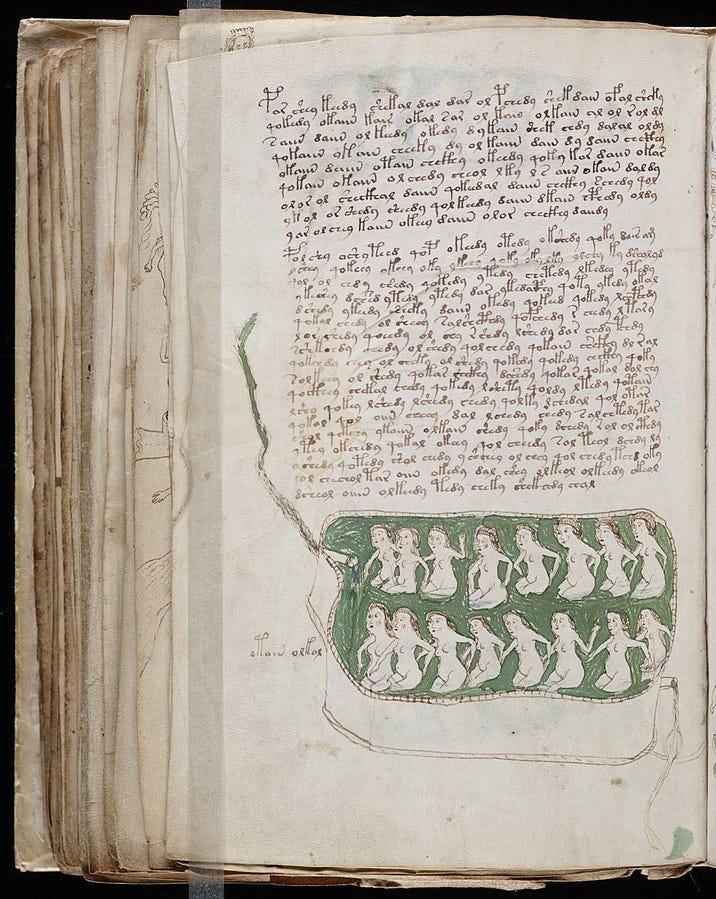

For those who are not as interested in historical curiosities as I am, the Voynich Manuscript is a book from the late Medieval period written in a unique and undeciphered (and likely undecipherable) script, and it contains, among its many enigmatic features, images of plants and other seemingly biological phenomena that have no correspondence to anything in our natural world. Strangest and most notorious of all are the drawings of naked women standing thigh-deep in pools of green liquid.

A page from the Voynich Manuscript

On the internet, the Voynich Manuscript frequently comes up as a spooky unsolved question of history, like the origin of the Sea Peoples or the identity of D. B. Cooper. Though long a source of fevered speculation from cranks and pseudoscientists, it has also attracted the attention of more reputable scholars. A few years ago, the New York Review of Books published an article reviewing the existing research on the Voynich Manuscript, and concluded that it must have been part of an elaborate hoax to swindle a nobleman out of money, or else the work of a madman.

But the unnamed narrator of Mircea Cărtărescu's novel Solenoid disagrees with these conclusions. After he is given a copy of the Voynich Manuscript by a mysterious librarian, he decides that it has “a meticulousness of transcription that made the idea of it being a hoax or a demented person’s raving almost totally implausible.” There is something real about the Voynich Manuscript - something true.

For the narrator, the contents of the manuscript are less significant than the web of connections it is a part of. The Voynich Manuscript gets the name from the rare book dealer Wilfrid Voynich, who was married to Ethel Lillian Voynich, the author of The Gadfly, an exceedingly popular historical romance. Ethel Voynich was herself the daughter of George Boole, an influential mathematician, and the sister of Alicia Boole Stott, who was, along with her husband Charles Howard Hinton, an important figure in the study of the fourth spatial dimension. And it is the fourth dimension which the narrator believes explains both the otherworldly strangeness of the Voynich Manuscript, and the otherworldly strangeness of his own life.

Solenoid was first published in Romanian in 2015 and now has been translated by Sean Cotter and issued by Deep Vellum Press.1 Despite the acclaim he has received in many European countries, Cărtărescu has had a bumpy path to the English language: the translation of the first book of his three-part meganovel Blinding was published by Archipelago in 2013, but the translations of the second two volumes have not yet been announced, likely due to low sales. It was only when The Untranslated - a website dedicated to books unavailable in English and one of the internet’s most ambitious ventures in literary criticism - declared that “Solenoid is the greatest surrealist novel ever written” did momentum build for more of Cărtărescu. Even so, there was a span of five years between The Untranslated’s review and Solenoid’s appearing in English. It was worth the wait, but the wait was not worthy of it.

The novel takes the form of journals written by a schoolteacher in 1980s Bucharest. He would have a quiet, unremarkable life, were it not for his “anomalies” - his many encounters with phenomena that seem to defy the laws of our natural world of three dimensions. What if anything binds these anomalies together is never clear, but they form a whole catalog of the uncanny, of which the following is only a very partial list: as a young child, the narrator underwent a mysterious surgical operation that his mother subsequently denies ever took place; the structure of his house (shaped like a boat from the outside) constantly shifts and seems to defy physics; a janitor at his school vanishes in the middle of a field, possibly abducted by extraterrestrials; a giant bronze statue comes to life amid the pleas of a quasi-religious underground movement; an abandoned factory near his school contains within it, among other oddities, dioramas housing living specimens of parasitical bugs the size of bears.

Some of Solenoid's absurdities and surrealities seem derived from life in 1980s Romania, under the repressive dictatorship of Nicolae Ceaușescu, and its eeriness is especially dependent upon its depiction of Bucharest. The narrator describes Bucharest as a planned city, like St. Petersburg or Brasilia, only planned as a city of ruins. Reading the novel, we feel we understand intimately the city's labyrinthine government buildings and dilapidated trams, its “old brick factories on whose blind walls giant letters spelled NO SMOKING and LONG LIVE THE ROMANIAN COMMUNIST PARTY'' and "vast courtyards closed in by concrete fences'' with a "bareness that came from beyond the world itself." It is an almost black and white world, its few colors coming from contaminated milk that is tinted blue, the walls that are painted “Nile-green"2, and the red glows of the sunset.

Befitting the stasis and torpidity of communist Romania, Solenoid's protagonist is a largely inactive one, prone to observation and self-exploration over adventure. Though he once had ambitions to be a great writer, he is now resigned to his fate as a schoolteacher. He makes only halting attempts to investigate his anomalies. The plot, to the extent that there is one, unfolds slowly, episodically, with a dozen different strands gradually developing. It is rare that any chapter directly follows the events of the previous one.

If there is a singular thread running through novel's weirdness, it is the fourth dimension - not the dimension of time, but not exactly a fourth spatial dimension either, or at least a spatial dimension as we understand it. The fourth dimension, when perceived by our three-dimensional minds, often seems to twist and warp our sense of physical scale. Small objects become the size of whole humans. Human-sized objects - often humans themselves - become gigantic, while buildings take centuries to traverse. Or possibly, it is not objects that increase inside but humans that decrease in size when coming into contact with the fourth dimension. Our 3D minds can necessarily provide us with only illusions when it comes to encountering the fourth dimension. It is not just that a four dimensional being could see in ways our minds cannot conceive of - with a single glance at our narrator, it would see his face and chest and spine and muscles and the insides of his lungs and still-beating heart with the ease with which we can see all four sides of a square - but also, it could, just as easily, see and enter into parallel timelines, fantasy worlds, dreams. In reading Solenoid the boundaries between these other worlds and our own are never quite exact; at times, a scene will seem to take place in a completely mundane setting before gradually slipping into the totally hallucinatory.

Though frequently hallucinatory in content, Solenoid is surprisingly not hallucinatory in form. The riddles it presents are extremely complex, but on the surface it is not a baffling, disorienting book to read. The narrator's distinct voice carries us securely across its over 600 pages, in a style that is artful, balanced, even lucid. The sentences are not long, and they are free of dense abstractions. Solenoid is rarely indirect in the way that novels like The Ambassadors or JR are indirect. The occasional lapses into pure surrealism feel like controlled explosions in an otherwise stable structure.

Most of all, the prose is overwhelmingly beautiful. It is sensuous when depicting lice infections and decaying apartment blocks, picturesque when describing existential torment, hilarious when detailing the misery of an impoverished totalitarian country. The narrator's vision encompasses both the grand struggles and the quotidian travails of life. Here are selections from two of the novel’s most beautiful passages:

We were a sketch, a gesture across the cloth of existence, connected to it through billions of little threads. In a curious way, it could be said that we secreted it and wove it, as hardworking as those spiders in the forest that wove enormous webs. We wove reality, we were reality. And outside of that there was nothing.

***

I become a simple place of crossing, a stone around which flows water that belongs not to the stone but the world at large, much larger than itself: the yellow water has dug into the heart of the mountain, twisted through its karstic system, it rose and fell in the depths of tis groundwater aquifers, received the dead bodies of transparent spiders from its walls, and it sprayed into the light, throwing itself forward in foamy waterfalls.

The first passage tells of how, as little children, the narrator and his friends attempted to grasp the reality of death. The second passage is the narrator’s description of urinating.

Solenoid's translator, Sean Cotter, has already shown his excellence at turning Romanian into English with his rendering of Rakes of the Old Court, which required him to coin neologism after neologism of English-sounding words to imitate the original's adventurousness in Romanian. Except in a few sections, Cotter does not have to create neologisms to translate Solenoid. Many of the real English words in Cotter's Solenoid are quite obscure, but they are used with precision and exactitude.3 Cărtărescu’s range of reference is extremely wide; his style is always recognizable, whether it is in the passages containing the minute material details of particular situations or the ones with the most airy abstractions. At no point does this version of Solenoid lapse into the clunky, mannered style of so much English-translationese, and for that both Cărtărescu and Cotter deserve credit.

Cărtărescu’s dedication to his art has resulted in a novel that questions the value of novels themselves. The narrator calls literature a “hermetically sealed museum, a museum of illusionary doors, of artists worrying over the nuance of beige and the most expressive imitation of a knocker, hinge, or doorknob.” These doors, which literature paints on our brains, give us “first beatitude, then disappointment” because they do not allow us to “pass into the tactile space of beings other than you.” If we must read books, the narrator says, we must read “the unartistic and unliterary ones, bitter and incomprehensible books that their authors were crazy to write , but which flowed from their dementia, sadness, and despair like springs of holy water.” His own journal is “an anti-book, the forever obscure manuscript of an anti-author.”

What does one make of a book as beguiling as Solenoid? Dreams are central to the novel, and having read Solenoid feels like having gone through a long, inscrutable dream - a pleasurable experience, but a pleasure that has no corollary in our waking life. Solenoid is assuredly neither a hoax nor the ravings of a demented person. It is true. It is one of the 21st century’s greatest novels.

You will note that Solenoid falls nowhere near my 50 year rule for reviewing books in this newsletter. I am allowing it into my newsletter as the rare recent novel that I believe can stand side-by-side with the great works of the past. I may make more exceptions in future editions of this newsletter.

The word “Nile-green” occurs several times in Solenoid - perhaps it is a reference to the Nile-green pools of liquid that are found in the Voynich Manuscript.

Listen to this interview with Sean Cotter on the Beyond the Zero podcast for the (possibly apocryphal) story of Cărtărescu's childhood competitions with his sister to memorize the dictionary.