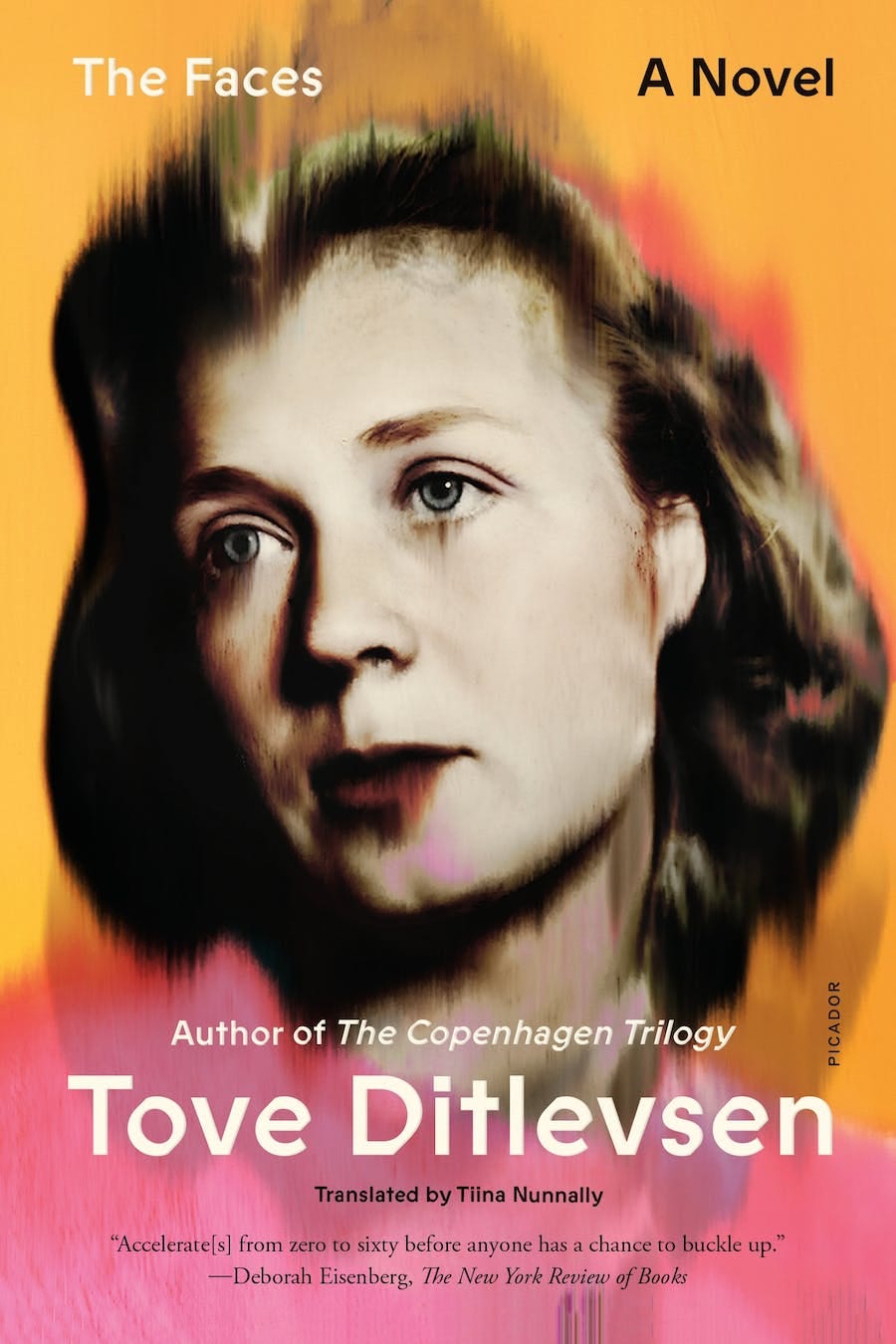

The Faces and The Trouble With Happiness by Tove Ditlevsen

Two newly translated books by Tove Ditlevsen

By Tove Ditlevsen; Translated from the Danish by Tiina Nunnally

144 pages. Picador. $16.00.

The Trouble with Happiness And Other Stories

By Tove Ditlevsen; Translated from the Danish by Michael Favala Goldman

192 pages. Picador. $26.00.

I.

I will not comment on the resemblances between Tove Ditlevsen’s life as she tells it in the Copenhagen Trilogy and the life of Lise, the protagonist of The Faces, except to note that there’s a type of person who cannot be found in The Copenhagen Trilogy but who seems to appear at every turn in The Faces: real shits.

In the first chapter of The Faces, Lise’s husband, Gert, comes home at night to tell his wife that Grete, his former mistress from his office, has committed suicide. His reaction reveals his utter callousness as both a husband and a human being: “It was a real shock. Not that it could damage my position, but you can see it’s damned embarrassing.”

“It’s your own fault” is how Gitte, their young housekeeper, approaches the subject when she talks to Lise about the suicide the next morning. Later in the day, Gitte tells Lise about her affair with Gert: “He doesn’t want an equal partner. It reassures him that, when all is said and done, I’m just his housekeeper.” Lise then talks with Nadia, her friend and a psychiatrist, who advises her to take sleeping pills.

By page forty, Lise has done just that: she has swallowed a large handful of pills and called her doctor to inform him of her suicide attempt. She wakes up in a hospital, where we encounter the novel’s shittiest person, the unnamed doctor who first sees Lise. When Lise tries to speak honestly and emotionally about her feelings, he reprimands her “jokes,” reminding her that “it costs the government 110 kroener a day to have you lying here.”

The remark that prompted the doctor’s reproach was Lise asserting that she attempted suicide because she had “such a terrible need to see some new faces.” This is of course nothing to be dismissed - it is a very telling response, in several ways. There is the obvious fact that she is exhausted with all the familiar people in her life, and the more subtle point that they exhaust her because they do not see her face - that they are so self-involved that they hardly notice her; she lives in a marriage where it is “part of their exhausting game that she never drew attention to herself.”

But there is another, more outré aspect to Lise’s remark. Before her suicide attempt, she had begun hearing voices, voices which do not seem to come from faces. She hears them in pipes in the bathroom, in walls, from people whose mouths aren’t moving. They are what some would call hallucinations, but Lise doesn’t refer to them in that way. They are simply another part of her world, to be contended with at some points and ignored at others.

The rest of the novel is consumed with how Lise deals with these voices. She is sent to a facility where she makes a few friends among the other patients there - and we are never quite sure how much these people are a part of her imagination and how much they are physically real fellow-travelers who share her affliction. By the end of the novel, she has both confronted the fears that produce her voices at a much deeper level and managed to better fake sanity for the people in her life. How much has she actually recovered? It’s left ambiguous, but I was not reassured by the final chapters.

The greatest achievement of The Faces is how deeply we understand Lise’s inner life in a novel composed of snappy dialogue and terse, pointed observations - no long, sinewy sentences of Jamesian complexity here. Unfortunately, The Faces never approaches the intensity we find in The Copenhagen Trilogy. It is quite short, and the ending is somewhat abrupt. It could have done with another act, another turn of the screw that would have added an extra dimension to Lise’s madness and the madness that surrounds her. Though far more enjoyable than some other widely praised slim novels in translation that have appeared in recent years, it is ultimately an insubstantial piece of work.

II.

The stories in The Trouble with Happiness might be said to have the opposite problem - they are a bit too substantial. They are so carefully constructed, with prose of such poise and characters of such depth, that they would no doubt get top grades in a creative writing workshop. That’s a bit too harsh, actually - what I really mean is that they distinctly recall the stories of John Cheever.

Indeed, there are some superficial similarities between Ditlevsen and Cheever: they both were born and died within ten years of one another, both grew up in economic precarity and never attended college, both ascended to their country’s literary elite thanks to powerful magazine editors, and both struggled with substance abuse in adulthood. Most significantly, the domestic plight of urban and suburban families - the unhappy marriages, the strained relationship between parents and children - serves as the principal subject of their short stories, and they are able to cast a sympathetic, knowing eye over the lives of both the working class and the upper-middle class.

But there is one difference between them that seems most crucial. In The Faces, Lise is an author of “fairy tales, short stories for little children, short novels about a childish girl’s fantasy world,” but there is nothing of the fairy tale in any of the stories in The Trouble with Happiness - unlike Cheever’s many fantastical tales such as “The Enormous Radio” or “Torch Song.” While it’s possible Ditlevsen wrote non-naturalistic stories that have not been included in The Trouble With Happiness, the ones in this collection are all disenchanted, free of anything but the bare facts of the material world.

There are some gems in the collection. “His Mother” is a basically plotless story of a young man who visits his mother with his girlfriend, but through small telling details in the quiet actions of the characters, we feel almost palpably their lifetimes of loss, disconnection, and disappointment. “The Knife” revolves around a father who passes down a treasured family knife to his son, who loses it. The father reveres the knife, and recalls how it set him apart from other boys in his childhood; and yet he strangely relishes the opportunity to discipline his son for losing the knife, to the point where we suspect he intended for his son to lose the knife.

Ultimately, the title and symbol of “The Knife” is ironic, for it is a story where nobody is stabbed, where interpersonal conflict is resolved discreetly, anticlimactically, and it works because the protagonist’s tough, masculine attitude ultimately fails to find a target. But that none of the stories in The Trouble with Happiness actually stab the metaphorical knife is something of a flaw in this collection.

Characters in Ditlevsen’s fiction (and this includes The Faces) rarely act decisively, hardly ever change their lives. It is difficult to imagine anyone in any of her stories committing a murder - most of them could not even manage a divorce. Her characters seem not to have any religious beliefs, or even any serious ideological commitments. Her prose alternates between an objective, removed third person prose style (often with an acidic or satiric stance) and a close, free indirect discourse. In some stories she balances these two styles quite nicely, but in others it feels as though all we have received is a bare recitation of facts.

“Life’s Persistence” is the title of one of Ditlevsen’s stories, and it would work just as well as the title of the collection. Its protagonist is a young woman trying to get an abortion after an affair with an older man, but when she sees the doctor, she cannot even work up the courage to ask for an abortion - he merely tells her that she is three months along in the pregnacny and shuffles her away. After she leaves, she feels like “herself again, her horrified soul reeling for support like a drunkard” as she walks alone to “her lonely rented room.” Alienation from others is something of a secret gift for Ditlevsen in The Copenhagen Trilogy, as it allows her to dive into the transcendent realm of literature; in her fiction it is a curse, and nobody ever seems to find an outlet for it. Is this what the trouble with happiness is?